115929

•

20-minute read

•

PageRank algorithm (or PR for short) is a system for ranking webpages developed by Larry Page and Sergey Brin at Stanford University in the late ‘90s. PageRank was actually the basis Page and Brin created the Google search engine on.

Many years have passed since then, and, of course, Google’s ranking algorithms have become much more complicated. Are they still based on PageRank? How exactly does the PageRank algorithm influence ranking, could it be among the reasons why your rankings have dropped, and what should SEOs get ready for in the future? Now we’re going to find and summarize all the facts and mysteries around PageRank to make the picture clear. Well, as much as we can.

Google PageRank (or Google page rank algorithm) is an algorithm used in SEO that ranks webpages based on the quantity and quality of backlinks to each page. In essence, each link to a page is a vote of confidence – pages with more high-quality inbound links are deemed more important, and thus rank higher in search results.

As mentioned above, in their university research project, Brin and Page tried to invent a system to estimate the authority of webpages. They decided to build that system on links, which served as votes of trust given to a page. According to the logic of that mechanism, the more external resources link to a page, the more valuable information it has for users. And PageRank (a score from 0 to 10 calculated based on quantity and quality of incoming links) showed relative authority of a page on the Internet.

How does PageRank work? In simple terms, PageRank works by treating each link to a webpage as a vote, and it shares the linking page’s score across its outbound links. The more high-quality links point to a page, the higher its own PageRank becomes. Google’s algorithm calculates this iteratively for all pages on the web, with a damping factor to account for random surfing.

Let’s have a more detailed look at how the PageRank algorithm works. Each link from one page (A) to another (B) casts a so-called vote, the weight of which depends on the collective weight of all the pages that link to page A. And we can't know their weight till we calculate it, so the process goes in cycles.

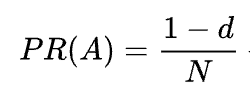

The mathematical formula of the original PageRank is the following:

Where A, B, C, and D are some pages, L is the number of links going out from each of them, and N is the total number of pages in the collection (i.e. on the Internet).

As for d, d is the so-called damping factor. Considering that PageRank is calculated simulating the behavior of a user who randomly gets to a page and clicks links, we apply this damping d factor as the probability of the user getting bored and leaving a page.

As you can see from the formula, if there are no pages pointing to the page, its PR will be not zero but

As there’s a probability that the user could get to this page not from some other pages but, say, from bookmarks.

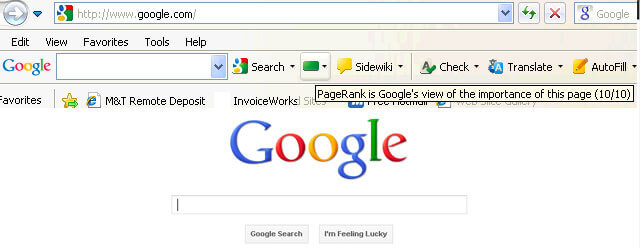

At first, PageRank score was publicly visible in the Google Toolbar, and each page had its score from 0 to 10, most probably on a logarithmic scale.

Google’s ranking algorithms of those times were really simple — high PR and keyword density were the only two things a page needed to rank high on a SERP. As a result, web pages were stuffed with keywords, and website owners started manipulating PageRank by artificially growing spammy backlinks. That was easy to do — link farms and link selling were there to give website owners a “helping hand.”

Google decided to fight link spam back. In 2003, Google penalized the website of the ad network company SearchKing for link manipulations. SearchKing sued Google, but Google won. It was a way Google tried to restrict everyone from link manipulations, however it led to nothing. Link farms just went underground, and their quantity multiplied greatly.

Besides, spammy comments on blogs multiplied, too. Bots attacked the comments of any, say, WordPress blog and left enormous numbers of “click-here-to-buy-magic-pills” comments. To prevent spam and PR manipulation in comments, Google introduced the nofollow tag in 2005. And once again, what Google meant to become a successful step in the link manipulation war got implemented in a twisted way. People started using nofollow tags to artificially funnel PageRank to the pages they needed. This tactic became known as PageRank sculpting.

To prevent PR sculpting, Google adjusted the PageRank algorithm in 2009 to change how nofollow links were treated, affecting how Google page rank flows through a site. Previously, if a page had both nofollow and dofollow links, all the PR volume of the page was passed to other pages linked to with the dofollow links. In 2009, Google started dividing a page’s PR equally between all the links the page had, but passing only those shares that were given to the dofollow links.

Done with PageRank sculpting, Google did not stop the link spam war and started consequently taking PageRank score out of the public’s eyes. First, Google launched the new Chrome browser without Google Toolbar where the PR score was shown. Then they ceased reporting the PR score in Google Search Console. Then Firefox browser stopped supporting Google Toolbar. Google PageRank updates became less frequent and eventually stopped – the Toolbar’s final PageRank update was December 2013. In 2013, the PageRank algorithm was updated for Internet Explorer for the last time, and in 2016 Google officially shut down the Toolbar for the public.

One more way Google used to fight link schemes was Penguin update, which de-ranked websites with fishy backlink profiles. Rolled out in 2012, Penguin did not become a part of Google’s real-time algorithm but was rather a “filter” updated and reapplied to the search results every now and then. If a website got penalized by Penguin, SEOs had to carefully review their link profiles and remove toxic links, or add them to a disavow list (a feature introduced those days to tell Google which incoming links to ignore when calculating PageRank). After auditing link profiles that way, SEOs had to wait for half a year or so until the Penguin algorithm recalculates the data. Even as Google refines its algorithms, the core PageRank site authority concept remains – which is why link schemes still aim to game Google’s PageRank algorithm with spam, though Google now better neutralizes those efforts.

In 2016, Google made Penguin a part of its core ranking algorithm. Since then, it has been working in real-time, algorithmically dealing with spam much more successfully.

At the same time, Google worked on facilitating quality rather than quantity of links, nailing it down in its quality guidelines against link schemes.

Well, we are done with the past of PageRank. What’s happening now?

Back in 2019, a former Google employee said the original PageRank algorithm hadn’t been in use since 2006 and was replaced with another less resource-intensive algorithm as the Internet grew bigger. Which might well be true, as in 2006 Google filed the new Producing a ranking for pages using distances in a web-link graph patent.

Yes – Google still uses PageRank as part of its core ranking system, though the algorithm has evolved since the early 2000s. Google representatives have confirmed that link analysis (PageRank) remains one of many ranking signals used internally. In fact, a leaked Google document from 2024 revealed that multiple updated versions of the PageRank algorithm (such as ‘RawPagerank’ and ‘PageRank2’) are still at work under the hood.

More to that, a former Google employee Andrey Lipattsev mentioned this in 2016. In a Google Q&A hangout, a user asked him what were the main ranking signals that Google used. Andrey’s answer was quite straightforward.

I can tell you what they are. It is content and links pointing to your site.

In 2020, John Mueller confirmed that once again:

Yes, we do use PageRank internally, among many, many other signals. It's not quite the same as the original paper, there are lots of quirks (eg, disavowed links, ignored links, etc.), and, again, we use a lot of other signals that can be much stronger.

As you can see, the PageRank algorithm is still alive and actively used by Google when ranking pages on the web. Furthermore, PageRank doesn’t just impact ranking – it also affects how Google crawls and indexes your site. Pages with higher PageRank tend to be crawled more frequently, as Google uses link popularity as a clue for crawl demand. Likewise, if you have duplicate versions of a page, Google is likely to choose the one with the stronger PageRank (more incoming link authority) as the canonical version to index

What’s interesting is that Google employees keep reminding us that there are many, many, MANY other Google ranking factors. But we look at this with a grain of salt. Considering how much effort Google devoted to fighting link spam, it could be of Google’s interest to switch SEOs’ attention off the manipulation-vulnerable factors (as backlinks are) and drive this attention to something innocent and nice. But as SEOs are good at reading between the lines, they keep considering PageRank a strong ranking signal and grow backlinks all the ways they can. They still use PBNs, practice some grey-hat tiered link building, buy links, and so on, just as it was a long time ago. As the PageRank algorithm lives, link spam will live, too. We do not recommend any of that, but that’s what the SEO reality is, and we have to understand that.

A 2024 Google leak confirmed PageRank is alive and well inside Google’s algorithm. In fact, Google uses several PageRank variants for different purposes – including a “Nearest Seed” version to evaluate content in clusters, and even references to the old Toolbar PageRank in internal systems. This proves that Google’s PageRank algorithm (in evolved forms) remains a foundation of how Google ranks pages in 2025.

On May 28, 2024, Google faced a massive leak of internal documentation. The leaked files provide an extraordinary glimpse into the inner workings of Google's Search algorithm, including the types of data Google collects and utilizes, the criteria for elevating certain sites on sensitive topics such as elections, and Google's approach to smaller websites.

The document has provoked a huge discussion about ranking factors — their number, their utilization, and why actually Google said that some of them are not counted at all.

Among others, the leaked data shed some light on the usage of PageRank.

Google employs several variations of PageRank, each tailored to serve distinct purposes within its ranking framework.

PageRank_NS (Nearest Seed) is a specialized version of the traditional PageRank algorithm, engineered to enhance document understanding and clustering. This variant aids Google in evaluating the relevance of pages within specific content clusters, making it particularly effective for categorizing low-quality pages or niche topics.

By clustering and identifying underperforming pages, PageRank_NS allows Google to assess their relevance and impact on your site’s overall quality with greater precision. If your site contains outdated or poorly performing articles, PageRank_NS can help Google distinguish them from your high-quality content, potentially mitigating their negative influence on your site’s rankings.

Understanding PageRank_NS provides an opportunity to create more focused and interconnected content structures. For example, if you run a blog on "healthy snacks," ensure your content is interlinked and relevant to other subtopics like "nutrition" and "meals on the go." This strategy enhances visibility in search results and establishes your content as authoritative within the niche.

Success hinges on strategically linking related content and maintaining high standards across all pages.

In addition to these advancements, the legacy of the old Toolbar PageRank still subtly influences page rankings. Despite Google’s public discontinuation of Toolbar PageRank in 2016, leaked documents reveal that variations such as "rawPagerank" and "pagerank2" continue to play roles in Google's internal ranking algorithms.

The leaked information also unveils a system called "NavBoost," which integrates data from multiple sources, including the deprecated Toolbar PageRank and click data from Google Chrome, to influence search rankings. This revelation contradicts Google’s previous public statements regarding the use of Chrome data for ranking purposes.

Moreover, these documents indicate that Google categorizes links into different quality tiers, with click data determining the tier and influencing the PageRank flow and impact on search rankings. While Toolbar PageRank is no longer a public metric, its legacy remains embedded in Google’s internal systems, shaping how links and user interactions affect search results.

Well, you got the idea that the PageRank algorithm now is not the PageRank it was 20 years ago.

One of the key modernizations of PR was moving from the briefly mentioned above Random Surfer model to the Reasonable Surfer model in 2012. Reasonable Surfer assumes that users don’t behave chaotically on a page, and click only those links they are interested in at the moment. Say, reading a blog article, you are more likely to click a link in the article's content rather than a Terms of Use link in the footer.

In addition, Reasonable Surfer can potentially use a great variety of other factors when evaluating a link’s attractiveness. All these factors were carefully reviewed by Bill Slawski in his article, but I’d like to focus on the two factors, which SEOs discuss more often. These are link position and page traffic. What can we say about these factors?

A link may be located anywhere on the page — in its content, navigation menu, author’s bio, footer, and actually any structural element the page contains. And different link locations affect link value. John Mueller confirmed that, saying that links placed within the main content weigh more than all the other ones:

This is the area of the page where you have your primary content, the content that this page is actually about, not the menu, the sidebar, the footer, the header… Then that is something that we do take into account and we do try to use those links.

So, footer links and navigation links are said to pass less weight. And this fact from time to time gets confirmed not only by Google spokesmen but by real-life cases.

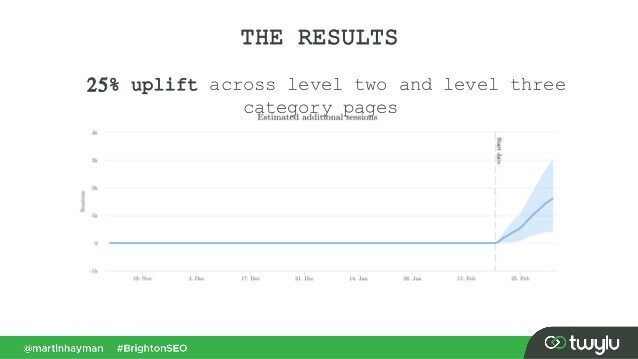

In a recent case presented by Martin Hayman at BrightonSEO, Martin added the link he already had in his navigation menu to the main content of the pages. As a result, those category pages and the pages they linked to experienced a 25% traffic uplift.

This experiment proves that content links do pass more weight than any other ones.

As for the links in the author’s bio, SEOs assume that bio links weigh something, but are less valuable than, say, content links. Though we don't have much proof here but for what Matt Cutts said when Google was actively fighting excessive guest blogging for backlinks.

John Mueller clarified the way Google treats traffic and user behavior in terms of passing link juice in one of the Search Console Central hangouts. A user asked Mueller if Google considers click probability and the number of link clicks when evaluating the quality of a link. The key takeaways from Mueller’s answer were:

Google does not consider link clicks and click probability when evaluating the quality of the link.

Google understands that links are often added to content like references, and users are not expected to click every link they come across.

Still, as always, SEOs doubt if it’s worth blindly believing everything Google says, and keep experimenting. So, guys from Ahrefs carried out a study to check if a page’s position on a SERP is connected to the number of backlinks it has from high-traffic pages. The study revealed that there's hardly any correlation. Moreover, some top-ranked pages turned out to have no backlinks from traffic-rich pages at all.

This study points us in a similar direction as John Mueller’s words - you don’t have to build traffic-generating backlinks to your page to get high positions on a SERP. On the other hand, extra traffic has never done any harm to any website. The only message here is that traffic-rich backlinks do not seem to influence Google rankings.

As you remember, Google introduced the nofollow tag in 2005 as a way to fight link spam. Has something changed today? Actually, yes.

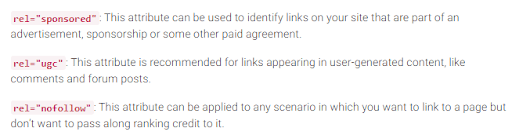

First, Google has recently introduced two more types of the nofollow attribute. Before that, Google suggested marking all the backlinks you don’t want to take part in PageRank calculation as nofollow, be that blog comments or paid ads. Today, Google recommends using rel="sponsored" for paid and affiliate links and rel="ugc" for user-generated content.

It’s interesting that these new tags are not mandatory (at least not yet), and Google points out that you don’t have to manually change all the rel=”nofollow” to rel="sponsored" and rel=”ugc”. These two new attributes now work the same way as an ordinary nofollow tag.

Second, Google now says the nofollow tags, as well as the new ones, sponsored and ugc, are treated as hints, rather than a directive when indexing pages.

In addition to incoming links, there are also outgoing links, i.e. links that point to other pages from yours.

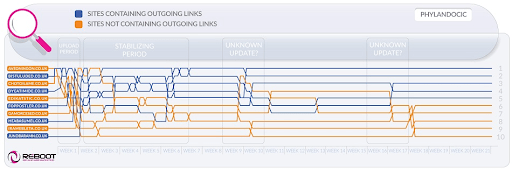

Many SEOs believe that outgoing links can impact rankings, yet this assumption has been treated as an SEO myth. But there’s one interesting study to have a look at in this regard.

Reboot Online carried out an experiment in 2015 and re-ran it in 2020. They wanted to figure out if the presence of outgoing links to high-authority pages influenced the page’s position on a SERP. They created 10 websites with 300-word articles, all optimized for an unexisting keyword - Phylandocic. 5 websites were left with no outgoing links at all, and 5 websites contained outgoing links to high-authority resources. As a result, those websites with authoritative outgoing links started ranking the highest, and those having no links at all took the lowest positions.

On the one hand, the results of this research can tell us that outgoing links do influence pages’ positions. On the other hand, the search term in the research is brand new, and the content of the websites is themed around medicine and drugs. So there are high chances the query was classified as YMYL. And Google has many times stated the importance of E-A-T for YMYL websites. So, the outlinks might have well been treated as an E-A-T signal, proving the pages have factually accurate content.

As to ordinary queries (not YMYL), John Mueller has many times said that you don’t have to be afraid to link to outer sources from your content, as outgoing links are good for your users.

Besides, outgoing links may be beneficial for SEO, too, as they may be taken into account by Google AI when filtering the web from spam. Because spammy pages tend to have few outgoing links if any at all. They either link to the pages under the same domain (if they ever think about SEO) or contain paid links only. So, if you link to some credible resources, you kind of show Google that your page is not a spammy one.

There was once an opinion that Google could give you a manual penalty for having too many outgoing links, but John Mueller said that this is only possible when the outgoing links are obviously a part of some link exchange scheme, plus the website is in general of poor quality. What Google means under obvious is actually a mystery, so keep in mind common sense, high-quality content, and basic SEO.

As long as the PageRank algorithm exists, SEOs will look for new ways to manipulate it.

Back in 2012, Google was more likely to release manual actions for link manipulation and spam. But now, with its well-trained anti-spam algorithms, Google is able to just ignore certain spammy links when calculating PageRank rather than downranking the whole website in general. As John Mueller said,

Random links collected over the years aren’t necessarily harmful, we’ve seen them for a long time too, and can ignore all of those weird pieces of web-graffiti from long ago.

This is also true about negative SEO when your backlink profile is compromised by your competitors:

In general, we do automatically take these into account and we try to… ignore them automatically when we see them happening. For the most part, I suspect that works fairly well. I see very few people with actual issues around that. So I think that’s mostly working well. With regards to disavowing these links, I suspect if these are just normal spammy links that are just popping up for your website, then I wouldn’t worry about them too much. Probably we figured that out on our own.

However, it doesn't mean you have nothing to worry about. If your website’s backlinks get ignored too much and too often, you still have a high chance of getting a manual action. As Marie Haynes says in her advice on link management in 2021:

Manual actions are reserved for cases where an otherwise decent site has unnatural links pointing to it on a scale that is so large that Google’s algorithms are not comfortable ignoring them.

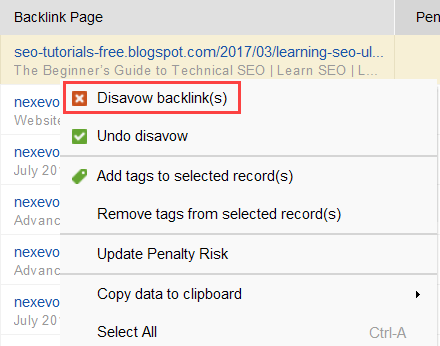

To try to figure out what links are triggering the problem, read through this guide on how to check backlink quality. In short, you can use a backlink checker like SEO SpyGlass. In the tool, go to Backlink Profile > Penalty Risk section. Pay attention to high- and medium-risk backlinks.

Download SEO SpyGlassTo further investigate why this or that link is reported as harmful, click the i sign in the Penalty Risk column. Here you will see why the tool considered the link bad and make up your mind on whether you’d disavow a link or not.

Download SEO SpyGlassIf you decide to disavow a link of a group of links, right-click them and choose Disavow backlink(s) option:

Once you’ve formed a list of links to exclude, you can export the disavow file from SEO SpyGlass and submit it to Google via GSC.

Speaking about the PageRank algorithm, we cannot but mention internal linking. Internal links help distribute PageRank SEO value throughout your site. The incoming PageRank is kind of a thing we cannot control, but we can totally control the way PR is spread across our website’s pages.

Google has stated the importance of internal linking many times, too. John Mueller underlined this once again in one of the latest Search Console Central hangouts. A user asked how to make some web pages more powerful. And John Mueller said the following:

...You can help with internal linking. So, within your website, you can really highlight the pages that you want to have highlighted more and make sure that they are really well-linked internally. And maybe the pages you don’t find that important, make sure that they are a little bit less linked internally.

Internal linking does mean a lot. It helps you share incoming PageRank between different pages on your website, thus strengthening your underperforming pages and making your website stronger overall.

As for the approaches to internal linking, SEOs have many different theories. One popular approach is related to website click depth. This idea says that all the pages on your website have to be at a maximum 3-click distance from the homepage. Although Google has underlined the importance of shallow website structure many times, too, in reality this appears unreachable for all the bigger-than-small websites.

One more approach is based on the concept of centralized and decentralized internal linking. As Kevin Indig describes it:

Centralized sites have a single user flow and funnel which points to one key page. Sites with decentralized internal linking have multiple conversion touchpoints or different formats for signing up.

In the case of centralized internal linking, we have a small group of conversion pages or one page, which we want to be powerful. If we apply decentralized internal linking, we want all of the website pages to be equally powerful and have equal PageRank to make all of them rank for your queries.

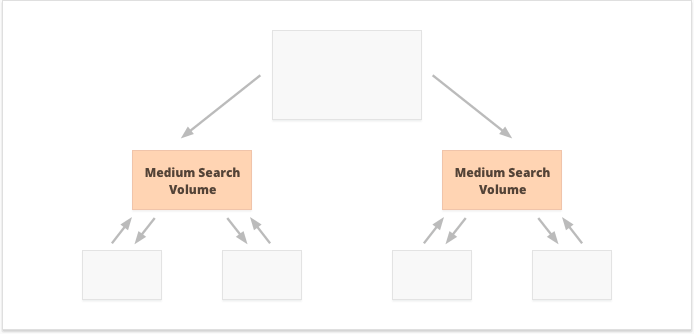

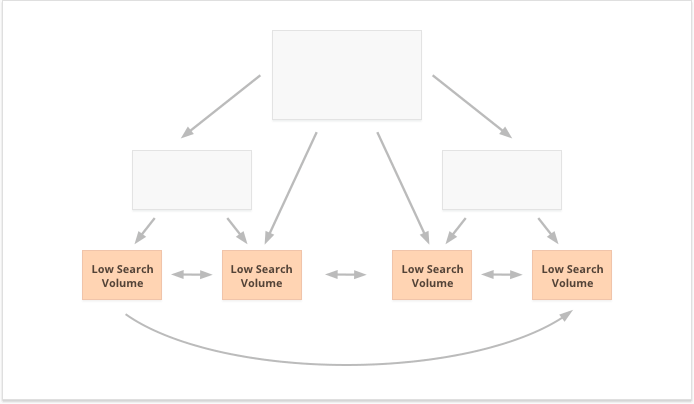

Which option is better? It all depends on your website and business niche peculiarities, and on the keywords you’re going to target. For example, centralized internal linking better suits keywords with high and medium search volumes, as it results in a narrow set of super-powerful pages.

Long-tail keywords with low search volume, on the contrary, are better for decentralized internal linking, as it spreads PR equally among numerous website pages.

One more aspect of successful internal linking is the balance of incoming and outgoing links on the page. In this regard, many SEOs use CheiRank (CR), which is actually an inverse PageRank. But while PageRank is the power received, CheiRank is the link power given away. Once you calculate PR and CR for your pages, you can see what pages have link anomalies, i.e. the cases when a page receives a lot of PageRank but passes further a little, and vice versa.

An interesting experiment here is Kevin Indig’s flattening of link anomalies. Simply making sure the incoming and outgoing PageRank is balanced on every page of the website brought very impressive results. The red arrow here points to the time when the anomalies got fixed:

Link anomalies are not the only thing that can harm PageRank flow. Make sure you don’t get stuck with any technical issues, which could destroy your hard-earned PR:

Orphan pages. Orphan pages are not linked to any other page on your website, thus they just sit idle and don’t receive any link juice. Google cannot see them and doesn’t know they actually exist.

Redirect chains. Although Google says that redirects now pass 100% of PR, it is still recommended to avoid long redirect chains. First, they eat up your crawl budget anyway. Second, we know that we cannot blindly believe everything that Google says.

Links in unparseable JavaScript. As Google cannot read them, they will not pass PageRank.

404 links. 404 links lead to nowhere, so PageRank goes nowhere, too.

Links to unimportant pages. Of course, you cannot leave any of your pages with no links at all, but pages are not created equal. If some page is less important, it’s not rational to put too much effort into optimizing the link profile of that page.

Too distant pages. If a page is located too deep on your website, it is likely to receive little PR or no PR at all. As Google may not manage to find and index it.

To make sure your website is free from these PageRank hazards, you can audit it with WebSite Auditor. This tool has a comprehensive set of modules within the Site Structure > Site Audit section, which let you check the overall optimization of your website, and, of course, find and fix all the link-related issues, such as long redirects:

Download WebSite Auditorand broken links:

Download WebSite AuditorTo check your site for orphan pages or pages that are too distant, switch to Site Structure > Visualization:

Download WebSite AuditorThis year the PageRank algorithm has turned 23. And I guess, it’s older than some of our readers today:) But what’s coming for PageRank in the future? Is it going to altogether disappear one day?

When trying to think of a popular search engine not using backlinks in their algorithm, the only idea I can come up with is the Yandex experiment back in 2014. The search engine announced that dropping backlinks from their algorithm might finally stop link spammers from manipulations and help direct their efforts to quality website creation.

It might have been a genuine effort to move towards alternative ranking factors, or just an attempt to persuade the masses to drop link spam. But in any case, in just a year from the announcement, Yandex confirmed backlink factors were back in their system.

But why are backlinks so indispensable for search engines?

While having countless other data points to rearrange search results after starting showing them (like user behavior and BERT adjustments), backlinks remain one of the most reliable authority criteria needed to form the initial SERP. Their only competitor here is, probably, entities.

As Bill Slawski puts it when asked about the future of the PageRank algorithm:

Google is exploring machine learning and fact extraction and understanding key value pairs for business entities, which means a movement towards semantic search, and better use of structured data and data quality.

Still, Google is quite unlike to discard something they’ve invested tens of years of development into.

Google is very good at link analysis, which is now a very mature web technology. Because of that it is quite possible that PageRank will continue to be used to rank organic SERPs.

Industry experts agree that Google is very unlikely to discard backlinks/PageRank after decades of development – it’s a “mature technology” that continues to underpin organic rankings. Google itself has indicated that while new signals (like user experience or semantic factors) matter, link-based authority is still fundamental for ranking most content in 2025.

Another trend Bill Slawski pointed to was news and other short-lived types of search results:

Google has told us that it has relied less on PageRank for pages where timeliness is more important, such as realtime results (like from Twitter), or from news results, where timeliness is very important.

Indeed, a piece of news lives in the search results far too little to accumulate enough backlinks. So Google has been and might keep on working to substitute backlinks with other ranking factors when dealing with news.

However, as for now, news rankings are highly determined by the publisher’s niche authoritativeness, and we still read authoritativeness as backlinks:

"Authoritativeness signals help prioritize high-quality information from the most reliable sources available. To do this, our systems are designed to identify signals that can help determine which pages demonstrate expertise, authoritativeness and trustworthiness on a given topic, based on feedback from Search raters. Those signals can include whether other people value the source for similar queries or whether other prominent websites on the subject link to the story."

Last but not least, I was pretty surprised by the effort Google’s made to be able to identify sponsored and user-generated backlinks and distinguish them from other nofollowed links.

If all those backlinks are to be ignored, why care to tell one from another? Especially with John Muller suggesting that later on, Google might try to treat those types of links differently.

My wildest guess here was that maybe Google is validating whether advertising and user-generated links might become a positive ranking signal.

After all, advertising on popular platforms requires huge budgets, and huge budgets are an attribute of a large and popular brand.

User-generated content, when considered outside the comments spam paradigm, is about real customers giving their real-life endorsements.

However, the experts I reached out to didn't believe it was possible:

I doubt Google would ever consider sponsored links as a positive signal.

The idea here, it seems, is that by distinguishing different types of links Google would try to figure out which of the nofollow links are to be followed for entity-building purposes:

Google has no issue with user generated content or sponsored content on a website, however both have been historically used as methods of manipulating pagerank. As such, webmasters are encouraged to place a nofollow attribute on these links (amongst other reasons for using nofollow).However, nofollowed links can still be helpful to Google for things (like entity recognition for example), so they have noted previously that they may treat this as a more of a suggestion, and not a directive like a robots.txt disallow rule would be on your own site.John Mueller's statement was “I could imagine in our systems that we might learn over time to treat them slightly differently.” This could be referring to the cases where Google treats a nofollow as a suggestion. Hypothetically, it is possible that Google's systems could learn which nofollowed links to follow based on insights gathered from the types of link marked up as ugc and sponsored. Again, this shouldn’t have much of an impact on a site's rankings - but it could theoretically have an impact on the site being linked too.

Q: What is a PageRank score?

A: It’s a value from 0 to 10 that Google’s PageRank algorithm used to assign to webpages based on link authority. Google no longer publicly shows these scores.

Q: What is meant by PageRank in SEO?

A: In SEO, PageRank refers to Google’s link-based ranking algorithm – basically a calculation of page importance via backlinks.

Q: Is PageRank still important for SEO?

A: Yes. Even though Google doesn’t display PageRank publicly, it remains a fundamental part of the algorithm, so building quality backlinks and a solid internal link structure is still critical for SEO.

Q: What is meant by PageRank in simple terms?

A: PageRank is basically Google’s way of measuring a page’s importance by its links. If a lot of authoritative sites link to your page, Google considers your page important (high PageRank).

Q: Does Google have a PageRank replacement metric?

A: Not for the public. Google retired the public PageRank score. SEO tools use replacements like Authority Score or Domain Authority to estimate page rank, but Google itself doesn’t show PageRank anymore.

I do hope I’ve managed to clarify the role of backlinks in Google’s current search algorithms. Some of the data I came across while researching the article was a surprise even for me. So I’m looking forward to joining your discussion in the comments.

Any questions you still have unanswered? Any ideas you have about the future of the PageRank algorithm?