Googling for Truth: The Invisible Ways Google Shapes Our Opinions

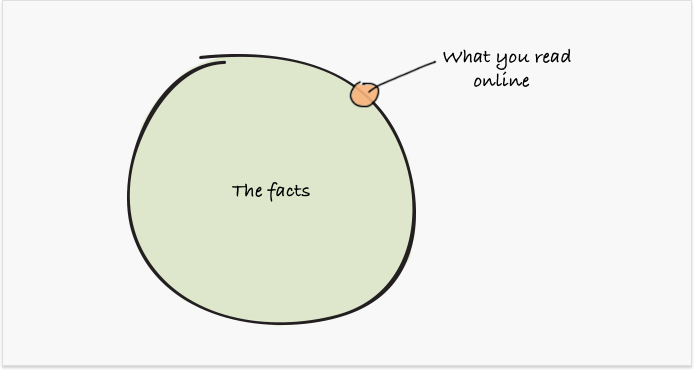

Google's results can be misleading, biased, or just wrong — and when we spot the obvious blunders, we tend to laugh them off. "That's alright, computers make mistakes". But what about the information that we don't know is incorrect or incomplete? And what about deliberate wrongness? Let's look into Google's search quality crisis, the possible reasons behind it, and the implications it has for how we form opinions about the world.

Google's been under fire lately. It started with a few rather innocent compilations of the (somewhat disturbing) blunders in its search results. Then, the quality of its search results has been seriously questioned; both its results and search suggestions have been seen as racist and sexist; it has been in the middle of the fake news scandal together with Facebook.

But what is really going on here? Is Google being negligent, or is it knowingly staying neutral and just presenting us the information that's out there, without too much censorship? Or, is it us? Are we asking too much of a search engine?

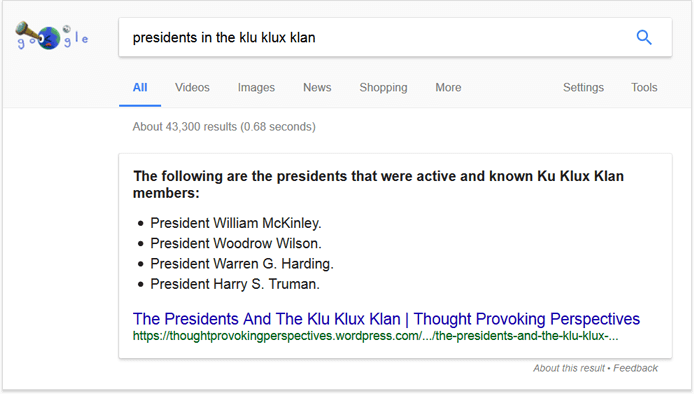

We've come to rely on Google, perhaps in more ways than we realize. We look up answers to simple questions like "what's the capital of Peru"; we go on and Google our health problems, hoping to find a cure. Sometimes we search for the dark, weird stuff, like whether or not some of the US presidents were members of the KKK. We Google things about politicians to make up our minds as voters. We feed our questions to an elaborate algorithm that goes on and gives us the best search results it can, and most of the time, we take the answers for truth.

Results that are just plain wrong

Source: The Next Web

There are plenty examples of Google's algorithm going wrong in various weird ways. This video offers a pretty brilliant compilation if you're looking for a taste.

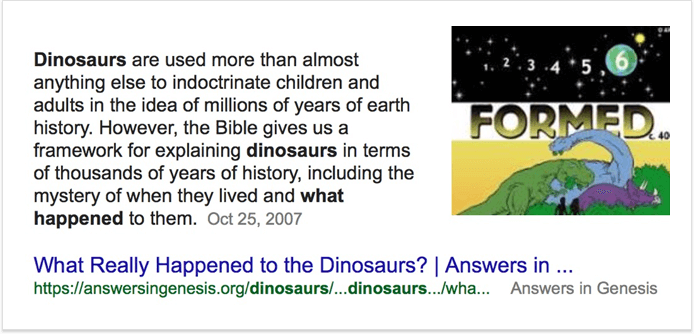

While some of these results may be funny, others are alarming, especially when you think of your kids coming across them. Google's featured snippets are supposed to offer the "one true answer" to an unambiguous question. And yet…

Source: Search Engine Land

The dangerous results

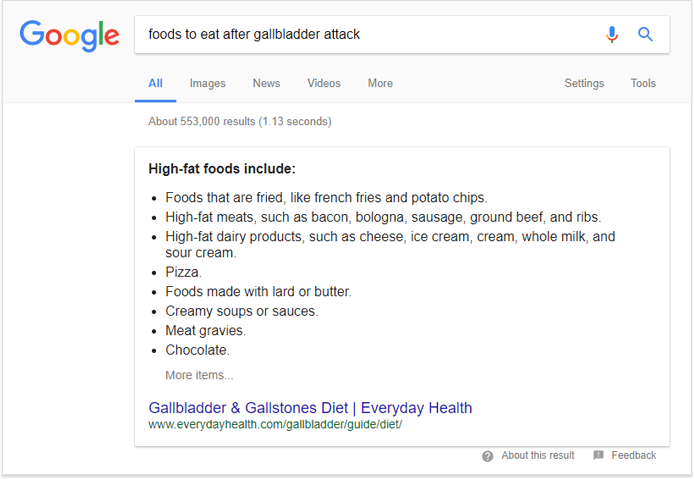

A few days ago, I was talking to a family member who'd recently had a gallbladder attack. Somewhat excitedly, they told me they were supposed to eat their favorite foods as part of the diet. Namely, the foods that are high in fat. I'm no gastroenterologist, but it sounded weird; I asked them where they got the advice from. Google, they said.

Let me make this clear: Google's result above lists the foods you should never eat if you recently had a gallbladder attack. In fact, these are the foods that will likely make your health problem much worse.

If you jump to the actual page the rich answer comes from, things get even more interesting. The page isn't even about the foods you can or can't eat after an attack; it's about your diet after you have your gallbladder removed through surgery (which is a whole different story). So effectively, when someone searched for "what can I eat if I have X health problem", they got a direct answer to "what can't I eat if I have Y health problem" instead, without realizing it.

Further down the search results for the same query, I found even more absurd, dangerous health advice under the "People also ask" section. "How do you remove gallstones naturally?" — "Mix and drink quickly, 4 oz. olive oil and 4 oz. lemon juice". A "natural" cure that will likely land you in the ER in a few hours.

Now think about all the health-related queries people make… About 1% of searches on Google are symptom-related. That's 55 million people googling their health problems every day. How often does Google get it wrong? We don't know.

Of course, having access to all this amount of medical information is life-changingly great. The problem is, 15% of searches Google processes every day are completely new. With 5.5 billion searches a day, it's next to impossible to avoid errors.

The question is, is Google supposed to give medical advice? Do we really need a direct answer result for those searches?

The discriminating results

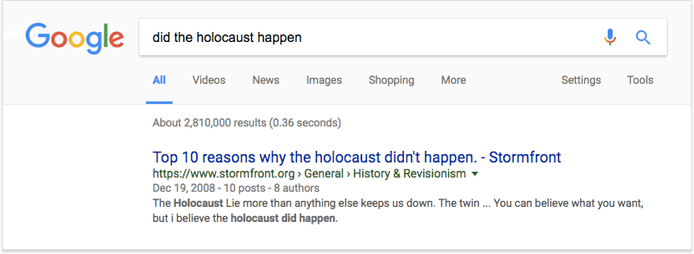

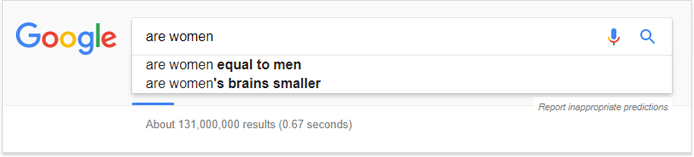

There's been a lot of examples of Google being sexist and racist lately. A bunch of them were highlighted in an article by The Guardian. Typing "are Jew"' in Google's search bar yielded an immediate "are Jews evil" suggestion (if you clicked on it, 8 of the top 10 search results would tell you yes, they are). The same happened for "are women".

Entering "did the hol" prompted an unsettling "did the holocaust happen" autocomplete suggestion; if you clicked on it, you'd find that a result titled "Top 10 reasons why the Holocaust didn't happen" ranked #1, coming from an American neo-Nazi website.

Source: Fortune

Google went on and quietly edited the most egregious examples published by The Guardian, but refused to explain its editorial policy or the basis on which it is tweaking its results.

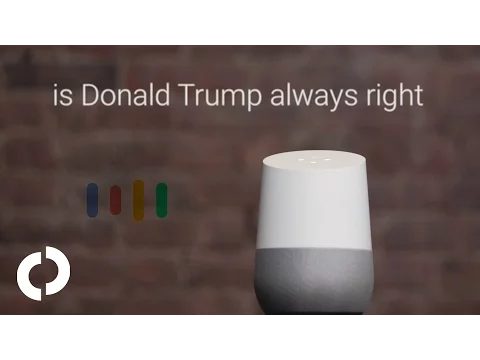

Did the selective editing solve the problem? The "are women evil" search suggestion — and the featured snippet which Google Home would gladly read to you — are indeed gone. But then:

These search results and autocomplete suggestions are just as disturbing as they are revealing. For some people — the ones who are deliberately asking Google whether Jews or women are evil — they must be opinion-shaping. Google — a powerful, objective information medium — gives them an instant affirmative answer. "Every woman has some degree of prostitute in her". "Judaism is satanic". Was Hitler evil? "Hitler was one of the good guys".

When the bad guys get good at SEO

Source: The Guardian

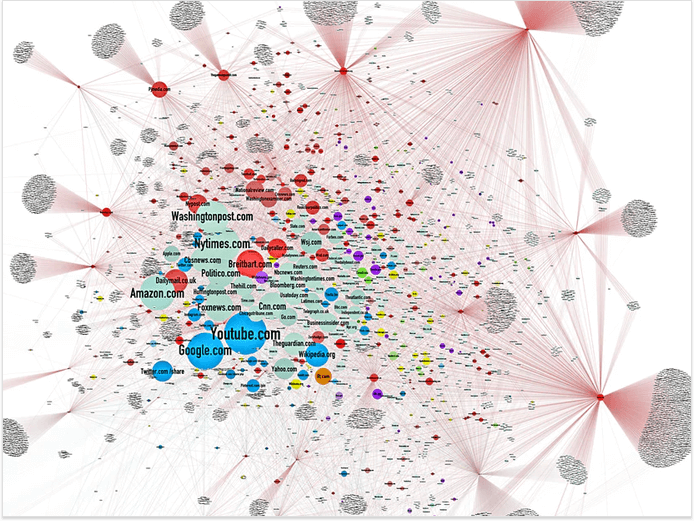

At this point, you must be wondering how the perplexing results above came about. You see, anyone with the right tools and knowledge can do SEO. Not just in the commercial niches, but in any space where you want to get your message across.

Jonathan Albright, an assistant professor of communications at Elon University in North Carolina, recently published his research on how rightwing websites had spread their message. He pooled over 300 fake news sites (the dark shapes on the map above) and scraped the links from the sites, a little like Googlebot does. He then scraped links from the sites that those sites linked to. And further on. He revealed 1.3 million hyperlinks that connect them together and into the mainstream media.

"So I looked at where the links went — into YouTube and Facebook, and between each other, millions of them… and I just couldn't believe what I was seeing."

According to Carole Cadwalladr of the Guardian, who spoke to Albright, the alt right fake news sites created a web of their own that is bleeding through on to our web: a system of hundreds of different sites that are using the same old SEO tricks that you're probably familiar with. A system that's developing "like an organism that is growing and getting stronger all the time."

At this point, the SEO is almost done. Once these sites have enough authority to rank, the fake news network is effectively an organism that feeds itself. As people search for information about Jews, Muslims, women, blacks, they will see derogatory search suggestions and links to hate sites. The more searchers click on those links (which will arguably help with the rankings in itself), the more traffic the sites get, and the more links and social media shares they accumulate. This is an infinite loop that helps the fake news ecosystem grow like a snowball. Albright calls this "an information war".

But the propaganda doesn't stop there. According to Albright, the rightwing sites he discovered are used to further track anyone who comes across their content.

"I scraped the trackers on these sites and I was absolutely dumbfounded. Every time someone likes one of these posts on Facebook or visits one of these websites, the scripts are then following you around the web. And this enables data mining […] to precisely target individuals, to follow them around the web, and to send them highly personalized political messages. This is a propaganda machine."

The censorship dilemma

Painting by Eric Drooker

Google's repeatedly said that it's a neutral platform; its algorithm does the job of matching a query with a list of results, making sure this match is as close as possible. It doesn't want to be seen as a publisher or content provider that should be governed by the rules that govern the media.

Frank Pasquale, professor of law at Maryland University, said he found Google's editing of the discriminative search results that the media picked up on a "troubling and disturbing development".

"They've gone on in the fly and plugged the plug on certain search terms in response to your article, but this raises bigger and more difficult questions. Who did that? And how did they decide? Who's in charge of these decisions? And what will they do in the future?"

But even if Google did come up with a censorship system that's open and effective, this wouldn't stop the debate. Most of us would still disagree with how they did it. Because morality is subjective.

There's another side to censorship, too. For the time being, it seems, Google might be one of the few objective sources of information about the society we live in; a ‘digital truth serum', as Seth Stephens-Davidowitz, author of "Everybody Lies", puts it. According to Stephens-Davidowitz:

"People tell Google things that they don't tell to possibly anybody else, things they might not tell to family members, friends, anonymous surveys, or doctors."

If Google was to censor its search results, and if it did a great job, a lot of us might at some point feel like we live in a safe, peaceful, tolerant place. It'd get extremely difficult to find out what is really going on in people's minds with all the violence and hate speech filtered out. Clearly, you don't want your kid to see those hateful search results and somehow figure those are "normal"' or "right" or "true"; but if Google censors out everything it deems politically incorrect… Will it be hiding a number of disturbing problems that need addressing?

Or is it already?

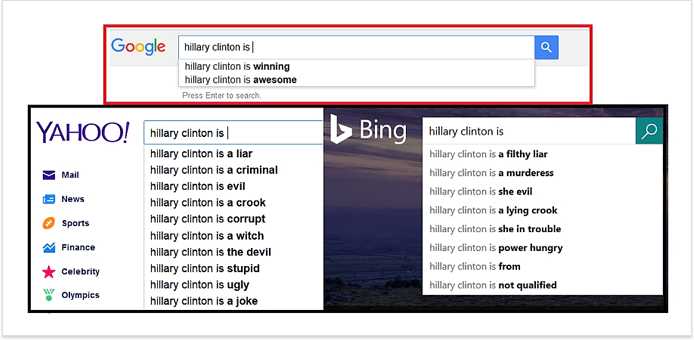

The good, the bad, and the selectively neutral

Source: Sputnik

Some of the mishaps above may have happened due to imperfections in the algorithm. Others — if you consider them mishaps at all — due to Google's lack of censorship. Or, rather, the selectivity of its censorship.

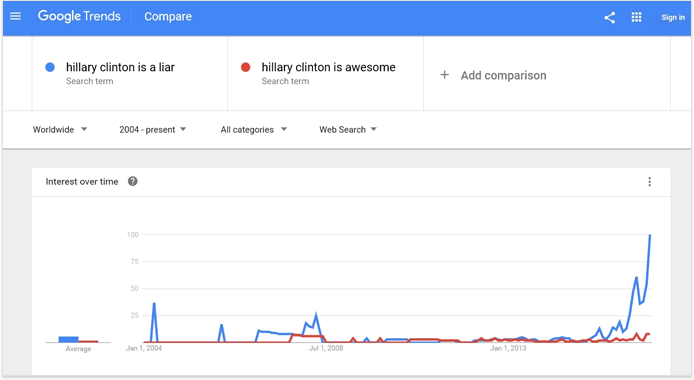

In a video by SourceFed, Matt Lieberman pointed at Google's altering search recommendations in favor of Hillary Clinton's campaign prior to the election. Searching for just about anything related to Clinton generated positive suggestions only. This occurred even though Bing and Yahoo searches produced both positive and negative suggestions, and even though Google Trends data showed that searches on Google that characterize Clinton negatively are far more common in some cases than the search terms Google was suggesting.

Source: Sputnik

And yes, it was just Hillary Clinton whose autocomplete suggestions appeared to be censored; Google did offer negative suggestions for Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump.

This is disturbing in more than a few ways. First, it may imply that Google is politically affiliated, despite its positioning itself as a neutral platform. But this isn't the big news: according to Google Transparency Project, Google's become one of the biggest spenders on government lobbyists in the US. In the United States, 251 instances of staff moving between senior positions at Google and the government were found.

Perhaps even more importantly, it means that Google is able to significantly shift our opinions, decisions, and actions by introducing a change as subtle as removing a few autocomplete suggestions.

Why we believe what we believe, and why any of this matters

When psychologist Robert Epstein first noticed the bias in some of Google's search suggestions, he started a research project to reveal how this could affect our behavior and opinions. The results were staggering: Epstein estimates that the biased search suggestions might have been able to shift as many as 3 million votes in the presidential election in favor of Hillary Clinton.

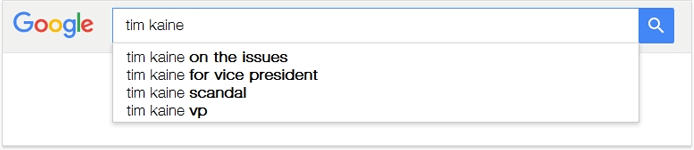

In the study, a diverse group of 300 people from 44 states across the USA were asked which of four search suggestions they would likely click on if they were trying to learn more about either Mike Pence, the Republican candidate for vice president, or Tim Kaine, the Democratic candidate for vice president. They could also select a fifth option in order to type their own search terms. Here is an example of what a search looked like:

Source: Sputnik

(Out of curiosity: which suggestion would you click on?)

Each of the negative suggestions ("Mike Pence scandal" and "Tim Kaine scandal") appeared only once in the experiment. Thus, if study participants were treating negative items the same way they treated the other four alternatives in a given search, the negative suggestions would have attracted about 20% of clicks in each search. But that's not what happened.

In reality, people clicked on the negative items 40% of the time — twice as often as one would expect by chance. What's more, with the neutral, negative suggestions were selected about five times as often. Among eligible, undecided voters — the impressionable people who decide close elections — negative items attracted more than 15 times more clicks than the neutral ones.

Perhaps less surprisingly, people who supported a certain political party selected the negative suggestion for the candidate from their own party less frequently than the negative suggestion for the other candidate. Simply put, negative suggestions attracted the largest number of clicks when they were consistent with people's biases.

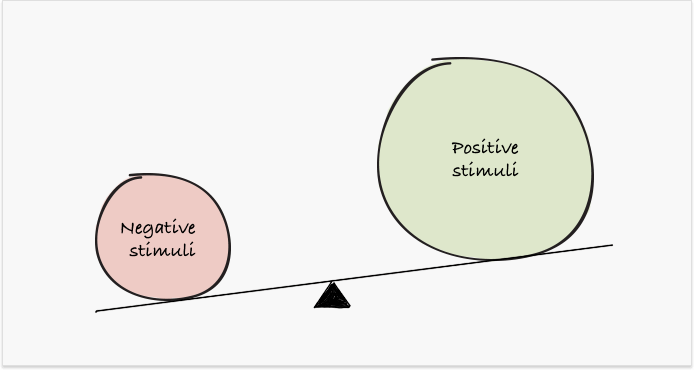

These findings are consistent with two well-known psychological biases: the negativity bias and the confirmation bias.

The negativity bias refers to the fact that negative stimuli have a greater effect on one's psychological state than positive ones, even when they are of equal intensity. The negative draws more attention, activates more behavior, and creates stronger impressions. In fact, political scientists have suggested that the negativity bias plays an important role in our political decisions: people often adopt conservative political views because they have a heightened sensitivity to negative stimuli.

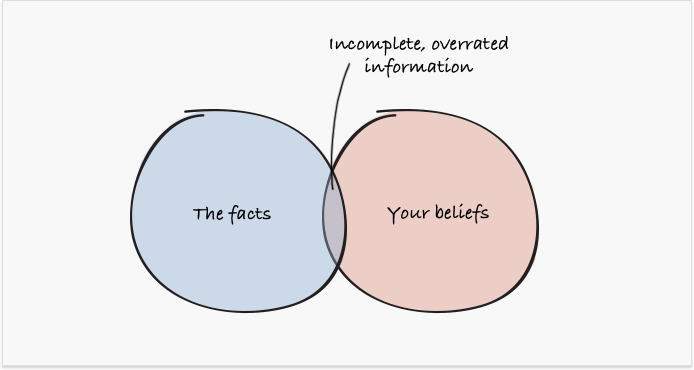

The confirmation bias refers to the fact that people almost always seek and believe information that confirms their beliefs, as opposed to information that contradicts those beliefs.

These biases explain why people are more likely to click on negative search suggestions than on neutral or positive ones, especially when the negative items are consistent with their own beliefs. According to Epstein:

"We know that if there's a negative autocomplete suggestion in the list, it will draw somewhere between 5 and 15 times as many clicks as a neutral suggestion. If you omit negatives for one perspective, one hotel chain or one candidate, you have a heck of a lot of people who are going to see only positive things for whatever the perspective you are supporting."

If the autocomplete suggestions can shift our opinions so much, what about the actual search results? In one of Epstein's recent experiments, the voting preferences of undecided voters shifted by 36.2% when they saw biased search rankings without a direct answer box. But when a biased featured answer appeared above the search results, the shift was an astounding 56.5%.

Epstein calls the impact of biased search results on our opinions the Search Engine Manipulation Effect (SEME). The effect is especially dangerous because it is invisible to users. Epstein and his colleagues found that it was possible to mask the bias on the first page of search results by including one biased search item in the third or fourth position of the results. This produced dramatic shifts in voting preferences that were invisible to voters — few or no people were aware that they were seeing biased rankings.

Whether or not it's Google's intention, it's shaping what we think about politicians, Jews, women, and the world. Google is the link between humans and information on the internet. Is the internet evil? Parts of it probably are. But if there's no universal way to define and measure evilness, how can we censor the evil out? Perhaps even more importantly, should we?

By: Masha Maksimava